THE XENARTHRANS

There are seven sloth species, ten anteater species, and 25 armadillo species.

The total number of extant species of xenarthrans may be surprising to many readers, as it was lower only a few years ago. The advent of new morphometric and, in particular, molecular techniques has rocked the stability of xenarthran taxonomy, resulting in important changes – a process that has only just begun and will certainly lead to additional taxonomic changes in the near future. New species have been described, while others revealed to be simply variations of the same species, thus leading to the combination of two species into a single one, a process known as synonymization.

Paleontological records suggest that all xenarthrans originated in South America, and the distributions of all current and extinct species have been confined to specific regions of the Americas, primarily South America.

A few can be found in Central America, but only one species, the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus mexicanus, formerly Dasypus novemcinctus), is present in the southern United States.

The 42 extant species represent only a small fragment of a much more diverse fossil assemblage that includes such famous oddities as giant ground sloths and glyptodonts.

Current molecular evidence indicates that the Xenarthra represent one of the four major clades of placental mammals.

THE XENARTHRANS

There are seven sloth species, ten anteater species, and 25 armadillo species.

The total number of extant species of xenarthrans may be surprising to many readers, as it was lower only a few years ago. The advent of new morphometric and, in particular, molecular techniques has rocked the stability of xenarthran taxonomy, resulting in important changes – a process that has only just begun and will certainly lead to additional taxonomic changes in the near future. New species have been described, while others revealed to be simply variations of the same species, thus leading to the combination of two species into a single one, a process known as synonymization.

Paleontological records suggest that all xenarthrans originated in South America, and the distributions of all current and extinct species have been confined to specific regions of the Americas, primarily South America.

A few can be found in Central America, but only one species, the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus mexicanus, formerly Dasypus novemcinctus), is present in the southern United States.

The 42 extant species represent only a small fragment of a much more diverse fossil assemblage that includes such famous oddities as giant ground sloths and glyptodonts.

Current molecular evidence indicates that the Xenarthra represent one of the four major clades of placental mammals.

There are two distinct groups OF Xenarthra:

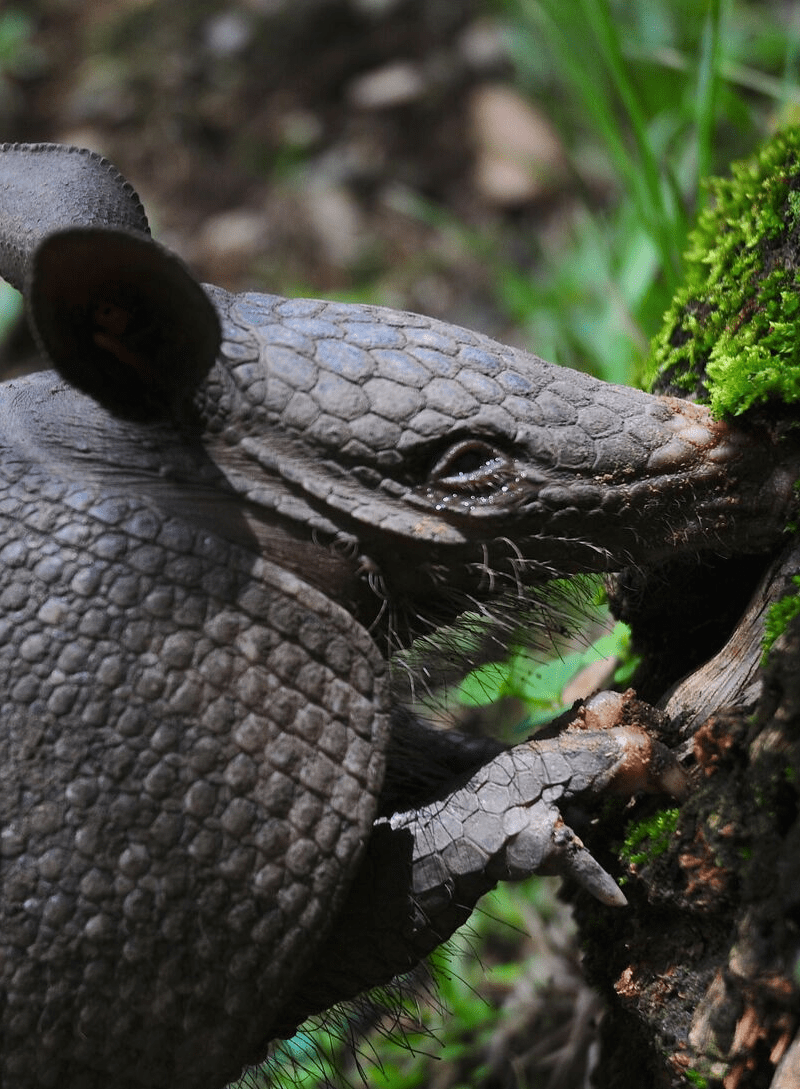

(1) The Cingulata, which include all modern-day armadillos (families Dasypodidae and Chlamyphoridae). They can be easily identified by the bony armor that covers their head, body, and tail (except in armadillos of the genus Cabassous, which have a naked tail). Although all armadillos feed on insects, some species also eagerly ingest other food items, such as plants, small vertebrates, or even carrion.

(2) The Pilosa comprise two groups:

2.1 Vermilingua, or anteaters (families Myrmecophagidae and Cyclopedidae): their most prominent feature is a long snout and a long, prehensile tongue that helps them capture ants and termites, their preferred prey. Anteaters lack teeth.

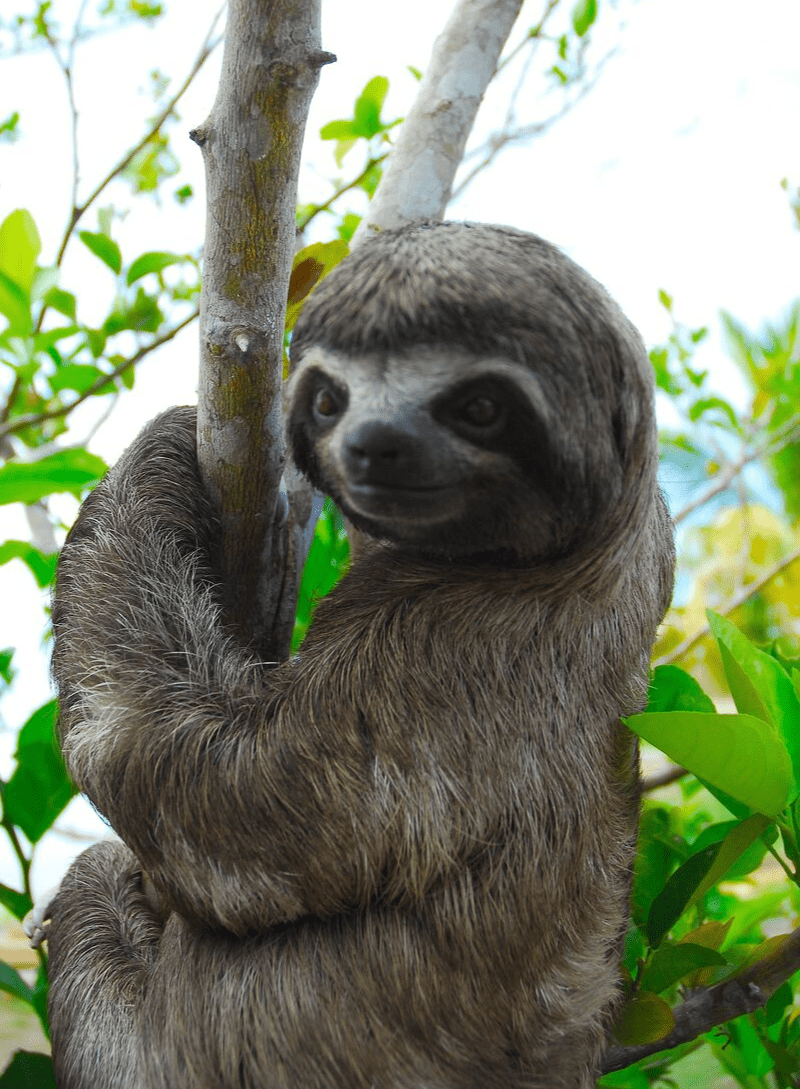

2.2 Folivora (= Tardigrada or Phyllophaga), or sloths (families Bradypodidae and Megalonychidae): modern sloths live almost exclusively in trees, while the large, prehistoric forms were terrestrial. Sloths are famous for their slow movements and uncanny ability to hide in the tree canopy. All extant sloths feed on plants.

Although at first sight armadillos, sloths and anteaters may look quite different, they have several similarities that led to their inclusion in the same superorder, the Xenarthra. For instance, they all have atypical joints between the vertebrae, from which the name Xenarthra was derived (xenos = strange, and arthros = articulation in Greek). These additional joints can only be found in armadillos, sloths and anteaters. All Xenarthra also have a reduced dentition, which is taken to the extreme in anteaters, which do not have any teeth. Sloths and armadillos have a variable number of simple, ever-growing teeth without enamel. Consequently, it is incorrect to call anteaters, sloths and armadillos “Edentata” (=toothless), as some people still do, as only anteaters are really toothless. Ironically, our Specialist Group’s newsletter and journal is called Edentata because that’s the name that was commonly used for this group until a few decades ago.

Some other unusual features shared among the Xenarthra are a low metabolic rate (which means that they use less energy than other mammals of the same size) and a low and variable body temperature.

Pangolins and aardvarks were historically grouped with anteaters, sloths and armadillos into a group called Edentata (=toothless). Molecular studies, however, confirmed that xenarthrans, pangolins and aardvarks are not closely related and evolved independently. Instead, their anatomical similarity represents an outstanding example of convergent evolution that reflects their common dietary specialization on colonial insects. Pangolins have been placed in a separate Order called Pholidota, while aardvarks now form the Order Tubulidentata.

We invite you to explore the fascinating world of armadillos, sloths and anteaters! In the species descriptions, you will find information on their biology, distribution, and conservation status, as well as the threats these charismatic animals are facing.

There are two distinct groups OF Xenarthra:

(1) The Cingulata, which include all modern-day armadillos (families Dasypodidae and Chlamyphoridae). They can be easily identified by the bony armor that covers their head, body, and tail (except in armadillos of the genus Cabassous, which have a naked tail). Although all armadillos feed on insects, some species also eagerly ingest other food items, such as plants, small vertebrates, or even carrion.

(2) The Pilosa comprise two groups:

2.1 Vermilingua, or anteaters (families Myrmecophagidae and Cyclopedidae): their most prominent feature is a long snout and a long, prehensile tongue that helps them capture ants and termites, their preferred prey. Anteaters lack teeth.

2.2 Folivora (= Tardigrada or Phyllophaga), or sloths (families Bradypodidae and Megalonychidae): modern sloths live almost exclusively in trees, while the large, prehistoric forms were terrestrial. Sloths are famous for their slow movements and uncanny ability to hide in the tree canopy. All extant sloths feed on plants.

Although at first sight armadillos, sloths and anteaters may look quite different, they have several similarities that led to their inclusion in the same superorder, the Xenarthra. For instance, they all have atypical joints between the vertebrae, from which the name Xenarthra was derived (xenos = strange, and arthros = articulation in Greek). These additional joints can only be found in armadillos, sloths and anteaters. All Xenarthra also have a reduced dentition, which is taken to the extreme in anteaters, which do not have any teeth. Sloths and armadillos have a variable number of simple, ever-growing teeth without enamel. Consequently, it is incorrect to call anteaters, sloths and armadillos “Edentata” (=toothless), as some people still do, as only anteaters are really toothless. Ironically, our Specialist Group’s newsletter and journal is called Edentata because that’s the name that was commonly used for this group until a few decades ago.

Some other unusual features shared among the Xenarthra are a low metabolic rate (which means that they use less energy than other mammals of the same size) and a low and variable body temperature.

Pangolins and aardvarks were historically grouped with anteaters, sloths and armadillos into a group called Edentata (=toothless). Molecular studies, however, confirmed that xenarthrans, pangolins and aardvarks are not closely related and evolved independently. Instead, their anatomical similarity represents an outstanding example of convergent evolution that reflects their common dietary specialization on colonial insects. Pangolins have been placed in a separate Order called Pholidota, while aardvarks now form the Order Tubulidentata.

We invite you to explore the fascinating world of armadillos, sloths and anteaters! In the species descriptions, you will find information on their biology, distribution, and conservation status, as well as the threats these charismatic animals are facing.