Greater long-nosed armadillo

(Dasypus pastasae)

other common names

–

Taxonomy

Order: Cingulata

Family: Dasypodidae

Subfamily: Dasypodinae

description

Until recently, Dasypus kappleri was a single species. Recent morphological, morphometric, and molecular analyses suggest that the former “D. kappleri” represents a species complex containing D. kappleri, D. pastasae, and D. beniensis.

Only exceeded in size by the giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus), the greater long-nosed armadillo has a head-body length of 51–58 cm and a tail length of 33–48 cm, and its carapace has 7–8 movable bands. It probably weighs around 8.5–10.5 kg, but it seems to be the smallest of the species of the “D. kappleri” complex. Apart from its size, it can be distinguished from other armadillos of the genus Dasypus based on the enlarged projecting scales at the knee; a wide base of the tail; and a lighter skin color on the part of the head that is not covered by the cephalic shield.

Compared to D. kappleri and D. beniensis, it seems that the scales on the pelvic shield of this species are non-uniform in size and have a rough texture, with the central scales being larger and standing up above the level of the smaller peripherals. Also, the posterior scales of the proximal rings on the tail are flattened.

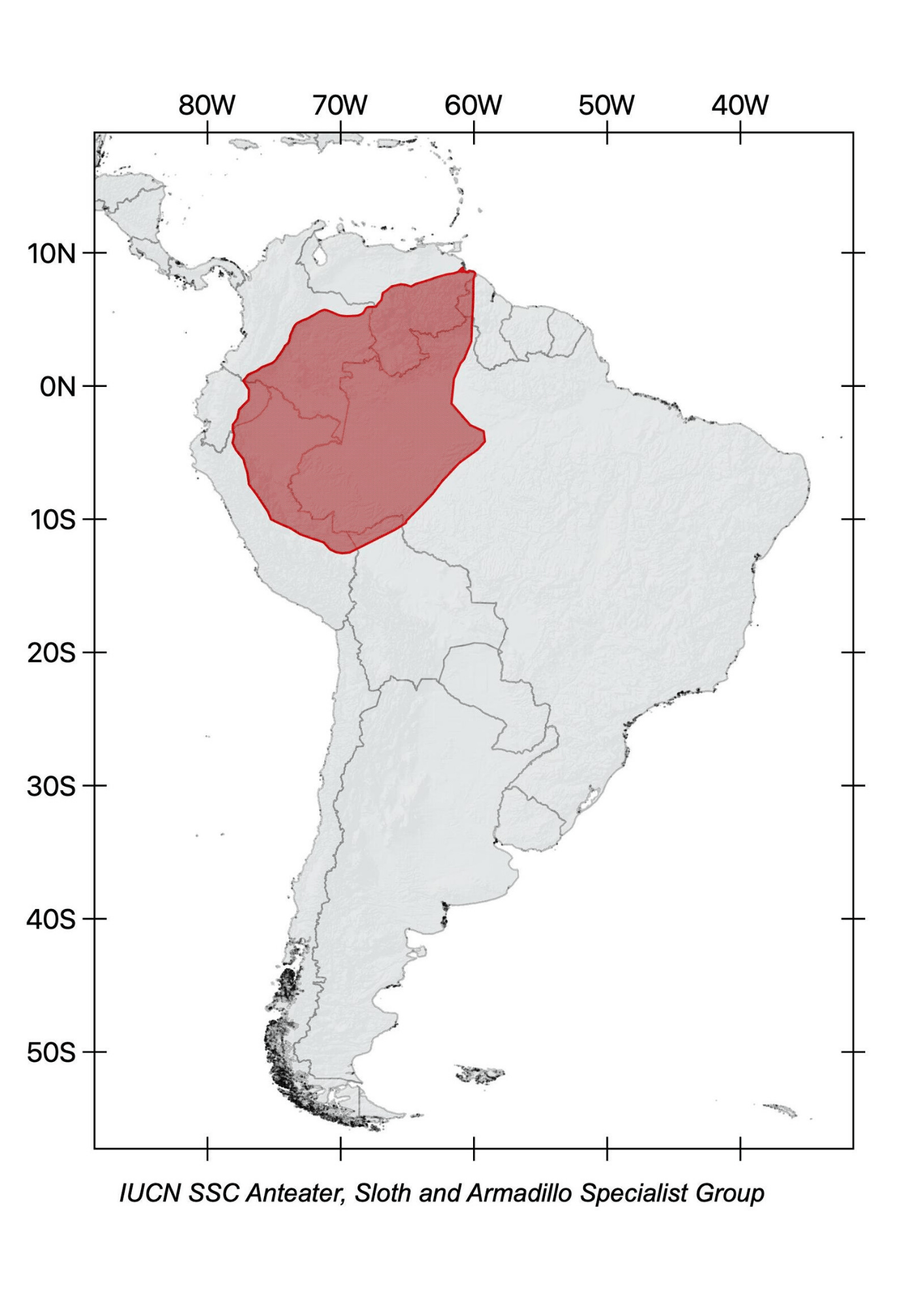

range

Dasypus pastasae can be found from the foothills of the eastern Andes in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela south of the Orinoco River into the western Brazilian Amazon, between the Madeira and Branco Rivers.

HaBITAT and ECOLOGy

Dasypus pastasae is restricted to lowland tropical rainforest. It has nocturnal habits, and is probably solitary and asocial.

diet

It is probably a generalist insectivore.

reproduction

Not much is known about the reproduction of greater long-nosed armadillos. Two offspring are born per litter. Anecdotal evidence suggests that they are always of the same sex, but it remains to be studied whether they are the result of polyembryony, as occurs in other species of the genus Dasypus.

curious facts

According to the Matses, an indigenous tribe that lives in northeastern Peru, greater long-nosed armadillos make a low rumbling growl when disturbed, and newborns whine inside the burrow. Additional indigenous knowledge about this species can be found in an article by David W. Fleck & Robert S. Voss, which has been published in Edentata 17 and is available here.

threats

The threats to this species have not yet been assessed, but it is probably affected by deforestation and hunting. It is unable to survive in savannas or open areas.

Population trend

Unknown.

conservation status

The extinction risk of this species has not been assessed since the new taxonomic classification. Hence, it should be considered Not Evaluated.